Guðriðr Þorbjarnardóttir “The first Norse women to travel to North America”

Guðríðr is undoubtedly one of the most interesting female figures of the Viking Period in the Nordic countries. Guðriðr received the nickname “viðförla” (literally “far traveled” or “wide-fared”) for having made numerous trips through-out her life that took her from her native Iceland to Greenland, to Vinland in the Americas, to Norway, to Rome …

We know about Guðriðr thanks to well-known Icelanders, some of them bishops, her descends, and because her travels were collected in two sagas: the “Saga of the Greenlanders” and the “Saga of Eirík the Red“). The sagas agree on most facts, although also with some divergence.

Guðriðr was born around 980 A.D. in Laugarbrekka, in Snæfellnæs, Iceland. She was the daughter of Þorbjörn Vifilsson and Hallveig.

Vifil, Guðríðr’s paternal grandfather, arrived in Iceland as an enslaved person. His master, Auð Ketillsdóttir gave him back his freedom and land. Although himself the son of a slave, Þorbjörn, Guðriðr´s father, did not allow her to marry the chosen, a young man named Einar who was the son of a slave. Perhaps to put land – or rather, the sea- between the lovers, her father sold the family farm in Iceland and emigrated with his family to Greenland. According to the “Saga of Eirík the Red”), Guðríðr accompanied Þorbjörn, her father, when he sold his land and decided to move to Greenland; they had to overcome storms and diseases that killed half the crew. Finally, the ship arrived at Hjerjolfnæs, in the Eirík Fjord, in Greenland, where they were welcomed by a farmer named Þorkel to spend the winter with him.

The “Saga of the Greenlanders” also recorded Guðriðr´s voyage to Greenland. This text, however, tells that Guðriðr was accompanied by her husband, Þórir Austmanni, a merchant of Norwegian origin. The ship in which they were traveling was shipwrecked on some reefs off the coast of Greenland. Fortunately, they were sighted by Leifr Eiríksson returning to Greenland after a trip to Vinland. Leifr picked up a group of fifteen castaways and invited them to bring as many of their belongings as the ship could carry. Leifr Eiríksson took them to Brattahlid and offered hospitality in his house to the couple and three other men; for the rest of the castaways he found lodging. It was from this event that Leifr received the nickname “the Fortunate”.

That winter, the crew of Þórir’s ship was attacked by illness and some of its members died and so did Þórir, Guðriðr’s husband.

We return to the “Saga of Eirík the Red”, which relates that Guðriðr was visiting the house of a farmer named Þorkel, who called a völva, a fortune teller named Þorbjörg. She prepared to perform the magic session, but for this she would need a woman to sing the so-called “Varðlokur” (“Psalm of the Occult“); they asked among the people on the farm, but no one knew the song, except Guðriðr.

Then Guðriðr said: “I am neither a connoisseur of magic nor a fortune teller, but in Iceland my adoptive mother, Haldis, taught me a song called “Varðlokur”. Þorkel responds, “Well, your knowledge has come to the right place.” And then she answered, “This is an enterprise in which I have no intention of helping you because I am a Christian woman.” Þorbjörg said to her: “It could be that you could help the people her by so doing , and you´d be no worse a woman for that. But I leave it up to Þorkel to procure what is necessary.” Þorkel insisted and she agreed to do as asked.

Then the women formed a circle around the hjalet, the elevated platform on which the völva would be seated while making her predictions. Guðriðr then song the chant beautifully. The völva thanked Guðriðr for the song and said that the spirits had arrived and had liked her singing so well performed: “Guðriðr, I want to reward you for the help we have received from you; now I can see your destiny completely clear. You are going to have a very honored marriage here in Greenland, although it will not be long-lasting, because your paths will take you to Iceland and from you will start a great and good lineage and, your offspring will shine such a strong radiance that I am not able to see exactly. May you fare well, now, my child.”

When the weather improved, Þorbjörn prepared his ship and they sailed to Brattahlíð, where Eirík the Red received them with joy and spent winter with him; when spring came, Eirík gave land to Þorbjörn in Stokkanæs, where he built himself a splendid farm and moved there to live.

Later, we are told that Þorstein, son of Eirík the Red, asked Guðríðr in marriage; they celebrated their wedding in Brattahlið. Þorstein owned half of a property called ”Clear Fjord Farm”; the other half belonged to a farmer also named Þorstein and his wife Sigrið.

Þorstein and Guðriðr spent the winter there, but an epidemic disease caused many deaths on the farm. Shortly after Þorstein Eiríksson also died.

This same episode is also recorded in the “Saga of the Greenlanders”, in which it is reported that Guðriðr was grief-stricken sitting in a chair in front of the bench on which Þorstein’s body had been placed. While she was comforted, Þorstein’s body stood up and said, “Where is Guðriðr?”; he said it three times, but Guðriðr remained silent. Then she asked Þorstein the Black, “Should I answer him? or not.” Þorstein the farmer said no. Then he sat in a chair with Guðriðr on his knees and said, “What do you want, namesake?”

Then, after a short pause, the dead man said: “I want to tell Guðriðr her fate, so that she will resign herself to my death, because I have gone to a good resting place. I can tell you Guðriðr, that you will marry an Icelander and that you will have a long life and many descendants, promising, bright and magnificent, sweet and very friendly. You will leave Greenland for Norway and from there to Iceland, where you will make your home. There you will live a long time and you will outlive your husband. You will travel abroad; you will go south on pilgrimage and return to Iceland to your farm, where a church will be built. There you will stay and take holy orders and die there.”

After this, Þorstein fell backward and his body was prepared. When spring came,Guðriðr returned to the Eirík Fjord carrying the bodies of Þorstein and the others who had died and the clerics officiated the ceremonies to receive Christian burial.

As we can see, the prophecy that Þorstein made about the future of Guðriðr was very similar to that which she received from the völva Þorbjörg in the “Saga of Eirík the Red”.

Guðriðr was invited to stay with Eirík the Red.

One autumn a wealthy Icelandic merchant named Þorfinnr Karlsefni Þordarsson arrived in Greenland; he came from Norway and was a man of a good family and a merchant with a good reputation, possessing a considerable fortune.

Þorfinnr commanded two ships loaded with goods and with a crew of about forty men. Eirík the Red invited Þorfinn and his men to the Christmas feasts; shortly afterward, Þorfinnr, in the presence of Eirík, asked Guðriðr to marry him.

Discussions about trips to Vinland must have been a recurring topic of conversation on the long winter nights. Some, including his own wife Guðriðr, urged Þorfinnr to make the journey. Once determined Þorfinnr hired a crew of sixty men and five women.

During the winter, Þorfinnr prepared an expedition to Vinland accompanied by two other ships; in total, a crew of about one hundred and sixty people.

When they left, they took with them all kinds of cattle, since, if possible, the intention was to settle in those lands. And Guðriðr accompanied her husband on the expedition; the couple sailed west to reach Vinland with their crew. When they arrived, they settled in the houses Leifr had built. There was born their son Snorri, the first European child born in America. They explored the lands further south and reached places that had not been reached by the expeditions that preceded them; they arrived at a place they called Hóp, which according to a climate specialist could be the island of Manhattan, where New York is now located. Guðriðr and Þhorfinnr spent three years on the American continent.

The colonization project failed and after fighting several battles against the native Indians,

Þorfinnr stated that he did not want to stay any longer in Vinland and wished to return to Greenland.

They prepared for the return trip and loaded the ship with many of the country’s products, including

grapes, berries, and skins. When spring came, they made the return journey without incident and

arrived in Eiríksfjord, in Greenland, where they stayed for the winter. Next, they travelled to Norway,

where they lived one winter and returned to Iceland. Here they settled in Glaumbær, where Þorfinnr

and Guðriðr had a son named Þorbjörn.

After Þorfinnr’s death, Guðriðr took over the management of the property together with her son Snorri, who had been born in Vinland. When Snorri married, Guðriðr undertook a journey abroad and made a pilgrimage south – probably to Rome – and then returned to her son Snorri’s farm. Meanwhile, he had a church built in Glaumbær. Afterwards, Guðriðr became a nun and stayed there for the rest of her days.

Snorri Þhorfinnsson, Guðriðr’s son in America, had a daughter whom he named Hallfrid and a son he

named Thorgeir. Hallfrid was the mother of Thorlak, Bishop of Skállholt in southern Iceland; Thorgeir

was Ingvild’s father, the mother of the first Bishop Brand; and Björn Gilsson, one of the descendants

of her son Þorbjörn, he was also bishop of Hólar.

This exceptional woman, intelligent, respected, and recognized by her contemporaries, had a long

and intense life. She made long and exhausting journeys, at times dangerous, reaching places so far

away that very few people in her time had reach.

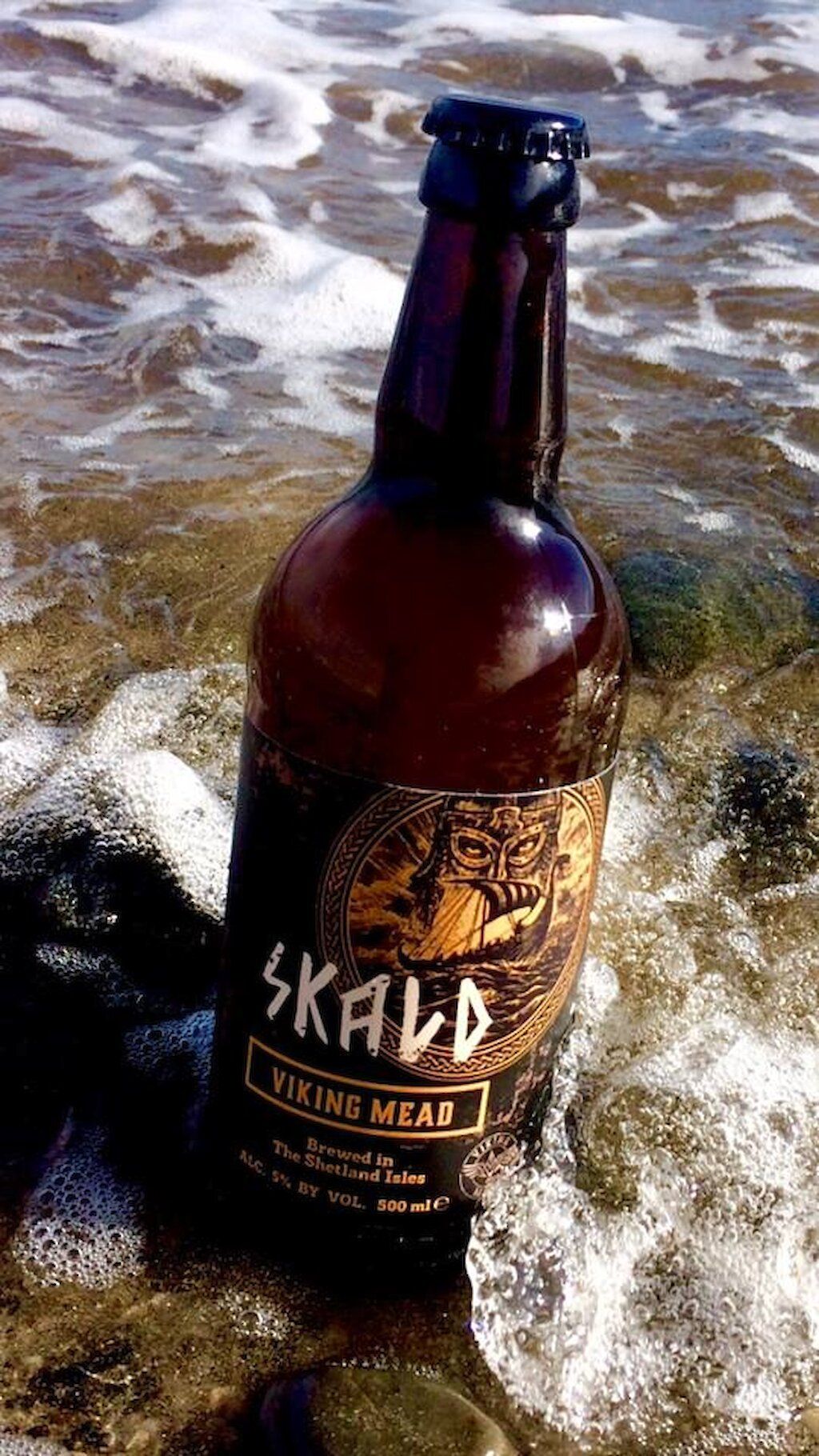

Wild yeast is unpredicable so it is difficult to say how it will perform and what the end result will taste like, but sometimes that’s half the fun. Fortunately, after checking on it anxiously over the course of a couple of days, I can see and hear signs of fermentation. The cloth is removed and the barrel is sealed with an airlock. After a couple of weeks, the mead is transferred to another barrel and left to age for a few months.

Wild yeast is unpredicable so it is difficult to say how it will perform and what the end result will taste like, but sometimes that’s half the fun. Fortunately, after checking on it anxiously over the course of a couple of days, I can see and hear signs of fermentation. The cloth is removed and the barrel is sealed with an airlock. After a couple of weeks, the mead is transferred to another barrel and left to age for a few months.

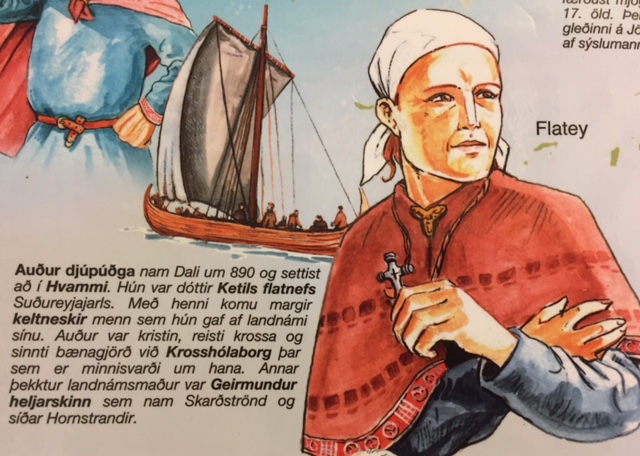

Aud the Deep-Minded. It’s a woman’s name. Yes, really. It captivated me too when I first heard it on the 1st of February 2015 at Sumburgh airport in Shetland.

Aud the Deep-Minded. It’s a woman’s name. Yes, really. It captivated me too when I first heard it on the 1st of February 2015 at Sumburgh airport in Shetland.

It’s time for the vegetables. Finely chopped parsnips and onions give you a good broth to cook the meat in. Put the meat in and make sure to have the pot boiling. Now is the time to chop some more wood if you didn’t do it this morning, because this is going to take a while (or just have a snow ball fight as we did).

It’s time for the vegetables. Finely chopped parsnips and onions give you a good broth to cook the meat in. Put the meat in and make sure to have the pot boiling. Now is the time to chop some more wood if you didn’t do it this morning, because this is going to take a while (or just have a snow ball fight as we did).